Braga Fresh, the home of Josie’s Organics, is a third-generation vegetable farm spread across 20,000 acres in California. Roughly 30 years ago, its owners made the bold move to transition their home ranch to organic, and today, 80% of the farm is certified organic by both the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and California Certified Organic Farmers.

Out of a desire to further improve soil health and decrease greenhouse gas emissions, the company decided to take things to the next level: It began trialing regenerative agriculture practices with sweet baby broccoli and cilantro in 2020. Braga Fresh modified tractors to till at a shallower depth and reduced the number of times they passed through the field, minimizing soil disturbances. The company also planted Sudan grass, switchgrass, and Merced Rye between the crop rows to attract beneficial insects, improve water filtration, and absorb and sequester carbon dioxide (CO2).

1. Tillage at Shepherd’s Grain.

2. “Organic Produce May Contain Lady Bugs & Friends.”

While the company is not yet Regenerative Organic Certified, it is actively practicing regenerative agriculture on 70 acres — and seeing a positive environmental impact. Soil measurements revealed an 8% increase in the microbiome, the underground community of bacteria, fungi, and protozoa that help cycle nutrients. Forty-nine new microbial species have appeared since the trials began. Carbon monitoring also showed the soil is now storing up to 1,000 pounds of CO2 — the equivalent of 504 pounds of coal burned — per acre.

But there have been challenges. A 14-acre crop of sweet baby broccoli grown with reduced tillage and companion planting had a 3% loss rate, almost double that of a 14-acre organic control crop. As an organic farm, the company already had trouble meeting cosmetic specifications. Now, with regenerative practices, the proliferation of beneficial bugs like syrphid flies and green lacewings found their way into the packaged produce.

“Products were rejected at docking stations because they found ladybugs in the boxes,” Leigh Prezkop tells The Rooted Journal. Prezkop is the senior program specialist for food waste at World Wildlife Fund (WWF), which works to reduce humanity’s impact on the environment and reform the food system. The organization highlights this challenge in the seventh installment of its report series “No Food Left Behind,” which seeks to understand how an estimated 10 million tons of specialty crops — roughly a third of what’s grown in the United States — never gets harvested. Instead, Prezkop says, those crops are tilled back into the soil or left to rot on site or in a landfill. The latest report explores this problem within regenerative agriculture, an eco-friendly method that could be better for farmers’ bottom lines if the kinks can be ironed out.

“We’re surprised that there’s still a lack of focus on [food] loss when we’re talking about regenerative systems,” Prezkop says. “How can we talk about regen-erative systems without talking about the fact that we still have upwards of 40% of waste and loss happening on farms?”

Fresh Del Monte banana fields.

Last year, WWF’s Living Planet Report found that food production is the primary driver of wildlife habitat loss and that it has fueled an average 73% decline in monitored wildlife population sizes since 1970. Agriculture consumes a staggering 44% of the planet’s habitable land and, along with food processing and production, accounts for a third of greenhouse gases. Much of the habitable land is devoted to conventional farming practices like monocropping, a technique often used for corn and soy and which relies on synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides known to pollute soil and water. “We’re talking about wasted energy, wasted land, wasted water, wasted fertilizer,” Prezkop says. “It’s a root cause [of] biodiversity loss.”

The 2024 report emphasized the need to scale “nature-positive” food production to reduce environmental harm. Regenerative agriculture, defined as an organic-based “collection of practices that focus on regenerating soil health and the full farm ecosystem” by the Regenerative Organic Alliance, aligns with that goal. In January 2025, California adopted a broader definition that includes conventional farms and focuses on eight target outcomes, including building soil health and maintaining farmers’ and ranchers’ economic livelihoods.

Regenerative agriculture can include cover cropping, crop rotation, low or no tillage, composting, and rejecting chemical pesticides and fertilizers, among other practices. Some growers try to directly target biodiversity loss by cutting back on broad spectrum insecticides and increasing pollinator habitats, says Matt Jones, an ecologist who consults with WWF. “It’s also important that landscapes have just unfarmed land — natural or semi-natural spaces,” Jones says. “You can be a small organic farmer who’s got pollinator hedgerows throughout the entire thing, but if you’re in an absolute biological desert of conventional farms with no native habitat, it’s going to be really hard to foster that biodiverse community that you want.”

Beyond regen-erative agriculture’s ecological benefits, a growing body of evidence suggests a compelling financial case for adopting it, though transitioning isn’t easy. During the first five years, farmers can experience revenue losses due to lower yields and higher seed and machinery costs. But one 30-year study of no-till farming showed that yields can improve over time. Another study involving regenerative wheat farming in Kansas found the method has the potential to increase profits as much as 120% above those of conventional farming, resulting in a 15% to 25% return on investment over 10 years.

Still, scaling regenerative agriculture will have limited impact if farmers can’t figure out food loss. WWF estimates that as much as 40% of all food produced globally, about 2.7 billion tons, gets lost or wasted. Roughly 15% of all food grown — 1.3 billion tons, representing 4% of all anthropogenic greenhouse gas — never makes it off the farm.

This massive amount of waste is worth addressing as the world’s population barrels toward 10 billion in 2050. “We know that if we can reduce all loss and waste, we would have more than enough food to feed our global population,” Prezkop says.

Prezkop’s team at WWF wanted to figure out how food loss in regenerative farming stacks up against other farming methods, like conventional and organic. So they partnered with four conventional and organic producers — Braga Fresh, Shepherd’s Grain, Zirkle, and Fresh Del Monte — that were trialing regenerative practices. All hoped to improve soil health and profitability, whether by reducing tillage, companion planting, cover cropping, integrating pest management, or using fewer chemicals and herbicides.

Using WWF’s Global Farm Loss Tool, the producers tracked food loss and gathered financial and environmental data. Over two years, participants saw some environmental improvements, like better soil quality, improved pest control, more water retention, higher soil carbon levels, and a reduction in water and fertilizer use. Everyone made it through the transition without losing revenue, though there weren’t huge gains. For example, Braga Fresh cut its production costs per acre by roughly 12% by reducing tillage (which saved on diesel) and cover cropping (which lessened the need for fertilizer and water). But reduced tillage meant lower yields, and workers had to spend more time sifting through weeds, grass, and other companion plants alongside the crops.

Almost all participants faced high rates of food loss, though the cause is unclear. Prezkop says she isn’t surprised. Her team expected that some growers might struggle to meet cosmetic standards when adopting regenerative practices. Techniques like cover cropping, reduced tillage, and creating pollinator habitats attract more bugs, which can bruise or scar produce or sneak into the packaged product.

In some cases, the report says, rather than taking imperfect produce to market, Braga Fresh found it more profitable to till the crop back into the soil and replant a new one immediately. Because of the region’s mild climate, Braga Fresh can grow multiple harvests per year. The company was able to cover its losses through price premiums on its regenerative produce, which helped it stay profitable.

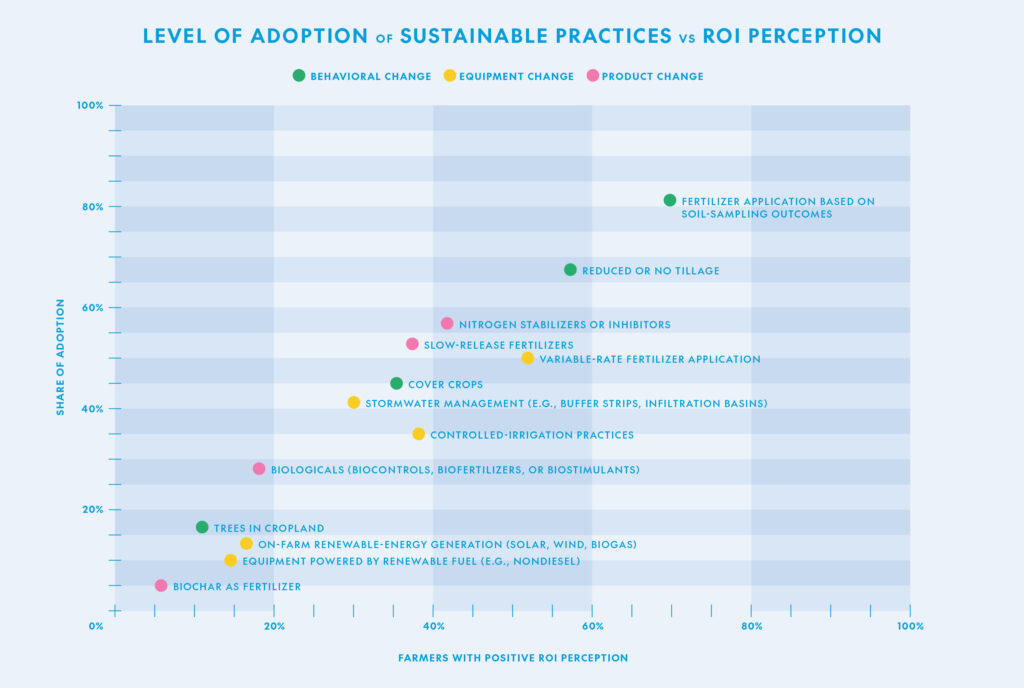

Farmers are more likely to adopt sustainable practices that they perceive to have positive ROI.

Nevertheless, the issue highlights food loss as yet another hurdle in scaling regenerative agriculture. “That’s a lot of potential loss we need to be thinking about,” Prezop says. “It’s going to be one of the risks of transitioning, and that’s why a lot [of growers] aren’t implementing more regenerative practices, because of that financial risk.”

WWF calls on buyers to support the regenerative transition through price premiums, which can help offset food loss, long-term contracts, and alternative finance models. But ideally, Prezkop would love to see farmers embrace circularity, a term that simply means making use of every part of the crop instead of letting it go to waste.

The idea is gaining traction in the food industry, particularly among some distributors and food manufacturers, Prezkop says. The Upcycled Food Association, which includes members like vitamin and supplement brand Garden of Life and premium tea purveyor Republic of Tea, focuses on repurposing food that would otherwise be lost. “It can be funneled down many different channels, whether the retailer uses it or it’s put into an upcycled item or animal feed or donation,” Prezkop says.

The first step is collecting more data. WWF’s report urges growers to measure what’s being left in the fields “early and often.” Knowing where and why loss happens can prevent waste and unlock unexpected business opportunities, Prezkop says.

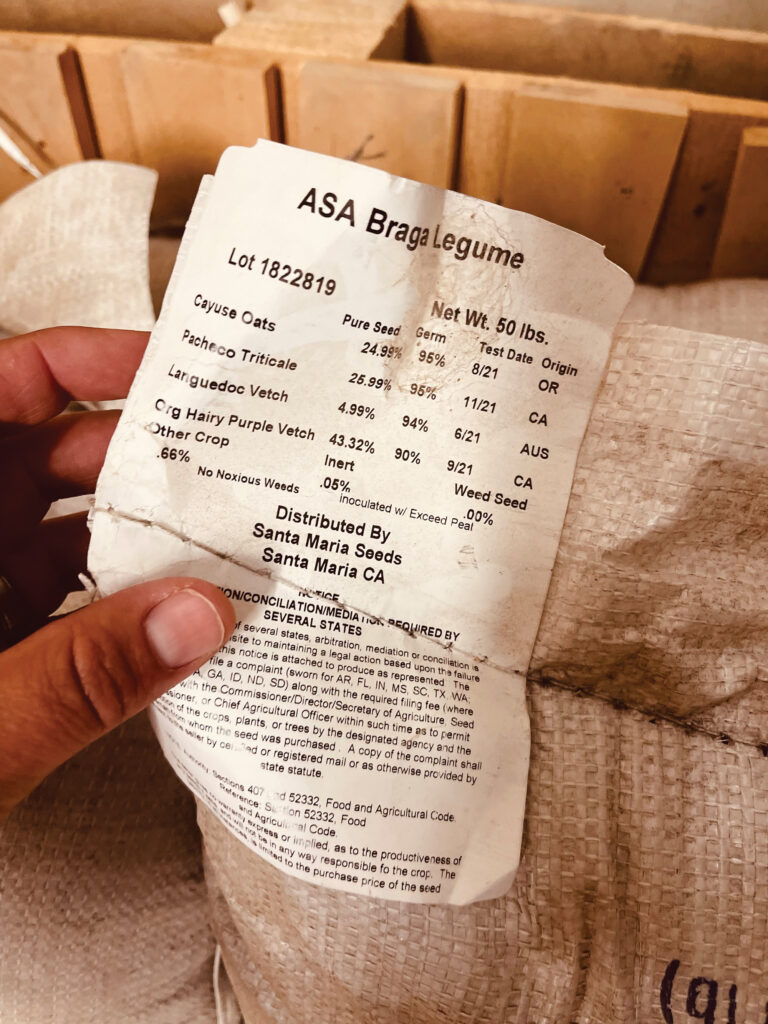

1. After first tillage at Braga Fresh.

2. Braga Fresh cover crop seed blend.

That’s exactly what happened at Fresh Del Monte’s conventional pineapple farms on the south Pacific coast of Costa Rica. Seventy-five percent of its fruit wasn’t making the export cut — leaving over 100,000 tons of residual pineapple. So the company invested in a processing facility to turn it into juice. The result? The company hasn’t sent any food to a landfill since 2022, and it’s saving more than $1 million annually on freight and fuel.

Even so, Prezkop believes circularity alone won’t solve the problem. The report recommends that buyers, aggregators, and retailers rethink rigid product standards. Although the USDA sets the baselines for those standards, retailers usually have additional qualifications. “If [growers] knew that ‘Okay, this buyer will still take this product even if it has blemishes,’ maybe they’d be open to trying these practices,” she says.

Braga Fresh has already started educating its buyers. On field visits, the company hands out flyers with illustrations of helpful insects. “Organic Produce May Contain Lady Bugs & Friends,” the flyer reads. “To grow without pesticides and support bee habitats, we apply beneficial bugs to our crops.”

Ultimately, Prezkop and Jones agree that consumers need to be part of the change. If shoppers knew what goes into growing sustainable produce and understood the magnitude of food waste and biodiversity loss, they might see minor blemishes — or even a ladybug crawling through their salad — in a new light.

“I’d like to think that if consumers knew what the trade-off was, they’d buy an apple that’s slightly less red but tastes just as good, rather than leaving that apple to rot in the field,” Jones says. “We have to be willing to support growers trying to implement these practices. We can’t expect food to look exactly the same as a conventional equivalent. We, as consumers, have to be a little more creative about what good food is.”